With a series of maps, infographics and data visualizations for non-linear reading, Bantustan is an example of ergodic and interactive literature. Readers can choose how to read the book: in the traditional linear fashion, or using the maps as visual interfaces for skipping from one story to another. You can track each of the written stories on the corresponding map, and you can also read the maps as pictorial stories.

All maps and visuals have been meticulously drawn by hand, digitally, using a drawing tablet. Maps represent a tapestry of pictograms, ideograms, writing systems, coats of arms, labyrinths, emblems, motifs, secret messages and other hidden symbols for the reader to discover and decipher.

As an illustration of how it works, here is the Chapter XIII map: Tanzania decoded.

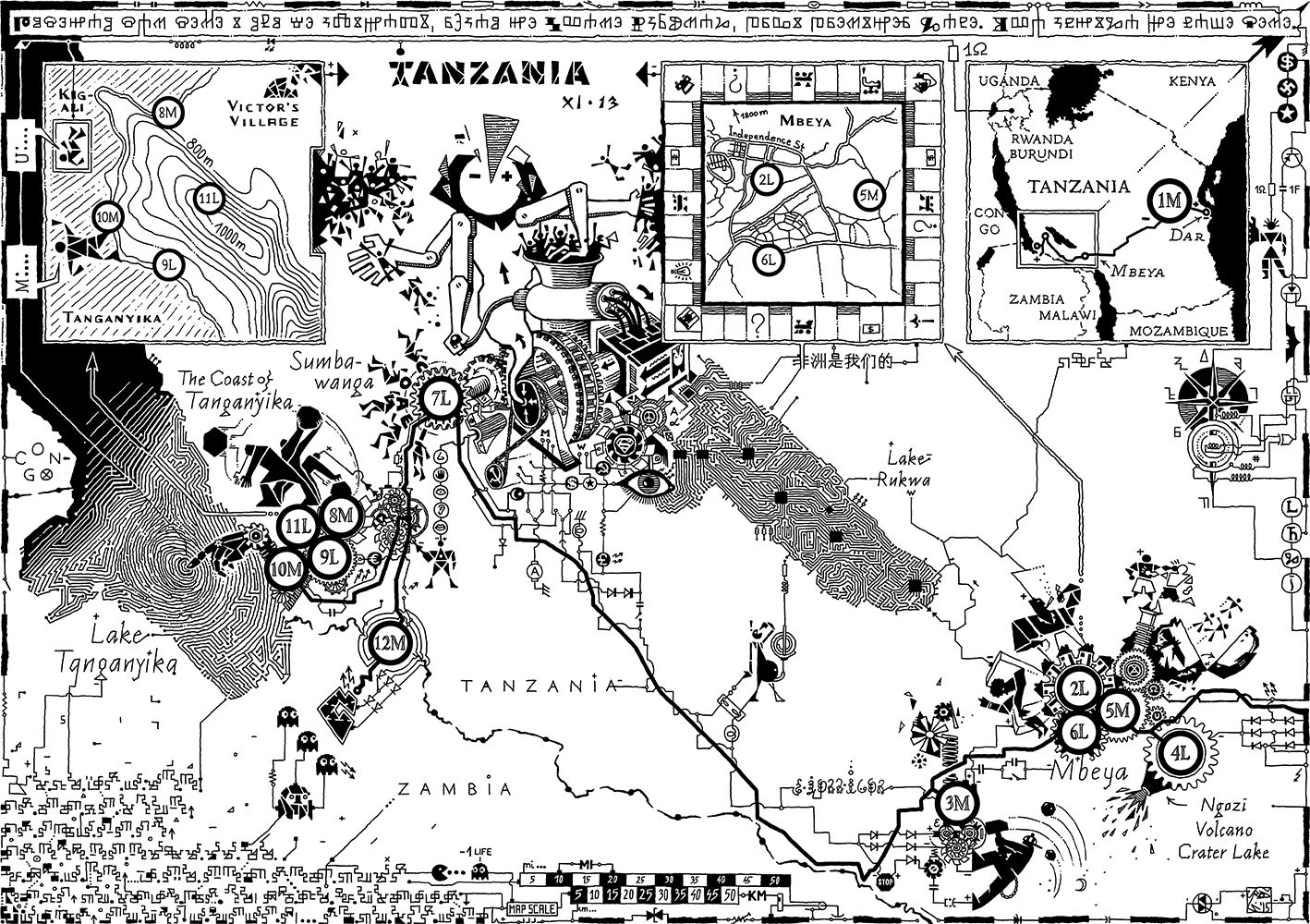

Chapter XIII map is, essentially, the map of southwestern Tanzania.

There is lake Tanganyika, to which Tanzania owes the first half of its name (Tan – ganyika and Zan – zibar), lake Rukwa, the city of Mbeya, and the village of Sumbawanga. You can see the land border with Zambia, and the lake border with D.R. Congo. The map tracks Lazar’s and Marko’s journey. Their route is marked with a thick black line, and their stories with numbers and initials (1M being the first story in the chapter, told by Marko). After parting ways with Uros in Kenya, Marko and Lazar travel from Dar Es Salaam to Mbeya, and then onwards to lake Tanganyika, finishing the chapter at the Zambian border, which stops them in their tracks, like an impenetrable wall.

The geographical map, however, hides a maze-like representation of Tanzanian history, a blueprint of an ideological machine that moves people around, grinding them along the way.

Even deeper, beneath the social layer, there is a story about personal bantustans, our own dungeons and cocoons, misunderstandings, the collisions of human particles, the yearning for touch.

Deutsch-Ostafrika. Fascism. British League of Nations mandate. Imperialism. United Republic of Tanganyika and Zanzibar. Nationalism. Ujamaa – African socialism. Panafricanism. Negotiations with the IMF. Liberal capitalism. Islamism. Jamhuri ya Muungano wa Tanzania.

Roads, shorelines, mountains and cities, isohypses and isobaths, fragments of electronic circuits – they are all just parts of this ideomachine. Ideological motifs are woven into the tapestry: from the communist star (the cogwheel itself is a symbol of socialist industrialization), to the pound and euro signs (to this day, Tanzanian money is still called shilling), to Superman and Batman (what are superheroes, if not romantical representations of privatized police and military forces?).

Can one ever break out of -isms?

In the machine-world, everything is measurable, and has its own unit of measurement. Distance is measured in kilometers and miles (thus the map scale). Pictures are measured in pixels. Resistance in ohms (Ω, Ohm).

What else is hidden in the belly of the machine?

Клином красным бей белых, Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge, a 1919 Soviet propaganda poster. A caricature of deus ex machina. The angel of history, Angelus Novus, a 1920 monoprint by Paul Klee. The influence the USSR had on the dreams of the African revolution. The cycle of power in the society, just like the hydrological cycle in the natural world.

The city of Mbeya with its volcano (the uphill road), its streets (Independence Street), and its three brothers, with whom Marko and Lazar will spend several days.

The youngest brother, Zukari, recites his hiphop lyrics: toothless ge-ne-ra-tion in safe re-si-gna-tion worthless ha-lu-ci-nation of a deluded na-tion ujamaa it is our soul it is what they stole gotta always stand tall gotta give it your all!

The middle brother, Taha, says: Fuck politics. Save yourself. Then he adds: And can you recognize, white man, the reek of every noble idea, every voluntary sacrifice, every big word? Can’t you tell what they all reek of? Carcasses!

The eldest brother, Kibelo, a man in a suit, looks down on them: Playing politics again, children? Good, that’s good. Just – take it easy, don’t get carried away!

The three Karamazov brothers pop out of Dostoevsky’s head.

In the meantime, Uros is in Kigali, in Rwanda, where he found a bizarre Chinese toy. When you push the button, two plastic boxers – one black, one white – start punching each other. Uros sends the photo of the toy to Marko, during online chat.

Lazar and Marko then travel to the volcano. My look crawls out of the window, into the quagmire and run-down villages. Cows drag themselves through the mud like emaciated carcasses. An old woman, hunched over, hauls a huge bunch of sticks on her back. Skinny children, in torn underwear and with distended bellies, stand by the road and wave. Kwashiorkor: the stomach of hunger. I wave back.

The stomach of hunger. Independence Street. A mawkish, big-dick kind of pride.

Numb with exhaustion, we reach the top of the volcano. The sun is setting on the opposite side of the crater filled with dirty water. Pain sprouts from my feet and grows inside me like a tree, climbing through my shins and knees, all the way to my temples.

After Mbeya, en route to lake Tanganyika, Lazar reads the book entitled Indigenous African Scripts, which he received as a gift from Doris in Nairobi.

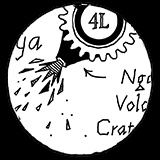

M, Mandombe. African script created in 1978. All the letters of this alphabet are derived from the figures 5 and 2. In the Lingala language, the word ‘mandombe’ means ‘for the black people’. Its creator, Wabeladio Payi from DR Congo, claimed that the script would lead to a rebirth of black Africa, creating a door through which African knowledge will be brought to the large company of universal human knowledge. Unfortunately, the Mandombe script remained limited to a narrow circle…

Wabeladio Payi invented the Mandombe alphabet following a prophetic dream, preceded by years of meditation. In his dream he saw himself sleeping, wearing blue trousers and a white shirt. A black insect started crawling over him, oozing black liquid. The liquid drew forms in the shape of the numbers 2 and 5 all over his body, until he was completely covered in it. Wabeladio woke up from his dream and exclaimed: “Oh, I have become a sign! I have become a letter! I have become a sign!”

The text in the bottom right corner of the map is written in the Mandombe script. It is the beginning of a prayer.

Instead of the cardinal directions, the compass rose has numbers, written in the Mandombe script.

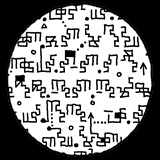

The text in the top margin is not the African Mandombe, but the Glagolitic alphabet, once used by the Slavic peoples of the Balkan Peninsula. The similarity is coincidental. Could the same be said of the similarities between Africa and the Balkans? Can you decipher the Glagolitic inscription? What does it say?

Can a writing system ever be independent of ideology? Isn’t every serif in reality something else – a dollar, a sickle (without a hammer), a crescent moon?

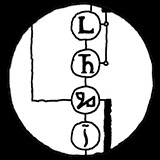

Plugged into the electronic circuit, there are also four letters from the four writing systems of the Western Balkans (two of them now extinct): Latin (L), Cyrillic (Ћ), Glagolitic (Ⰳ) and Arebica (ا).

People as vowels. People as screams. People enslaved by letters. “I have become a letter! I have become a sign!”

Until we reach a completely personal script, legible only to the person who invented it, Luigi Serafini, in order to write his atlas of an impossible, incommunicable world, Codex Seraphinianus. Isn’t every tiny segment of every letter of every alphabet a potential source of endless misunderstandings? Isn’t every serif – of the Serafini variety?

Chinese script is also there. Throughout the journey, we encounter numerous signs of Chinese expansion in Africa. The Chinese inscription says: “Africa belongs to us.”

Above the inscription, you can see the rim of the Monopoly board.

The map of Mbeya is framed within Monopoly, the board game. Chinese monopolism, Victor the tycoon, the Tanzanian state. Monopoly is played by skipping from field to field, just like reading Bantustan.

A human eye is also part of the big, ideology-generating machine. The eye of Horus, from Chapter IV, is used in the book as a symbol of our reductionist naivety, our intellectual laziness, our misplaced zeal. Our game of mystification, which we play with the world, and with ourselves.

Anything that has an eye, humans are likely to perceive as a face. Including this map.

The illustrator’s signature is also a part of the machine. This book, Bantustan, is itself a part of the machine. Can one ever break out of -isms?

Zukari, the youngest brother, rebels against the system, unaware that he is a part of it. Thus the sad emoji in the circuit.

The pictogram of Zukari was inspired by Soviet propaganda posters. The same is true of the mysterious stone-throwing man (story 11L). More about him soon.

Besides Batman and Superman, Pac-man is also in the machine. The whole book is a game (with its protagonists as game animals, constantly hunted by others, and by each other).

At the end of the chapter, Lazar and Marko are stopped at the border between Tanzania and Zambia. I’m sorry – Baldie hangs up – you can’t enter Zambia. Bureaucrats as Pac-man’s pixelized ghosts. The chapter ends with a question mark: will they be able to enter Zambia?

Tanzania: -1 life.

Lazar remembers his childhood story about the man without senses. For a brief moment, I remember a story I wrote as a kid, about a man who had none of the five senses but could sense the cardinal directions: North, West, South, East. And that man set off on a journey, following the lines of Earth’s magnetic field – lines that guided him like thin, fibrous touches on his skin.

Marko and Uros are chatting online (story 10M). Marko is at the shore of Lake Tanganyika, while Uros is all the way in Rwanda, in Kigali. Marko is trying to persuade Uros to come and meet up, but Uros is resisting. The line that connects them has a resistor (1Ω, not much of a resistance).

Lazar is alone, atop a hill. The isohypses look like cocoons that surround him, which he is unable to break out of. Bantustan as a personal bantustan – a one-man jail, the solitary confinement of self.

A mechanical hand. An electric lake. A fingerprint. The dream of touch.

With all the layers of social, racial, religious, ideological, geographical and other differences, with the sediments of historical garbage, with the linguistic impasses, with all the different scripts and sidetracks, to say nothing of individual differences and nasty personal dispositions – is contact even possible?

Is the story of bantustans – of prisons, cocoons, armors, isolated worlds – really a story of the (im)possibility of contact?

In a flash of lightning, I see someone walking down the center of the village. A muscular man, barefoot, in his underpants. The next flash reveals his twisted face and gaping mouth. Marko nudges me with his elbow. We hide deeper under the eave.

The man pulls a large rock out of the mud. He walks up to a hut and hurls it at the door. Baaam! Then he lifts it again and goes to another hut. Baaaam! No reaction from the inside. A cramp clutches at my stomach. I wish for a light to appear somewhere, for someone to come, for the rain and the night to end.

Wading through the viscous mud, the man hurls the rock a couple more times. His motions grow heavy, weighed down by the strain and the water, the thick membrane of darkness. We see him only for split seconds, in white bursts of light. He turns towards us. For a moment I lapse back into my nightmare about the giant Earth: we all live scattered, isolated, divided by chasms and desolate wastelands – hopelessly far from each other.

Please support The Travel Club on Patreon,

and help us make more stuff in the future.